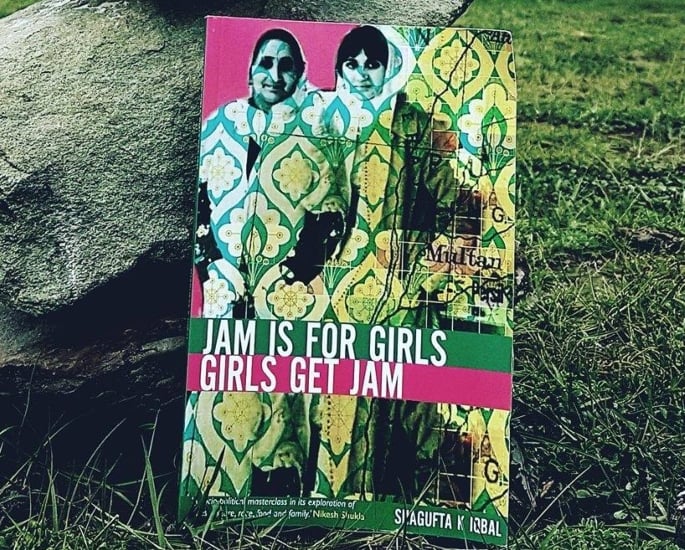

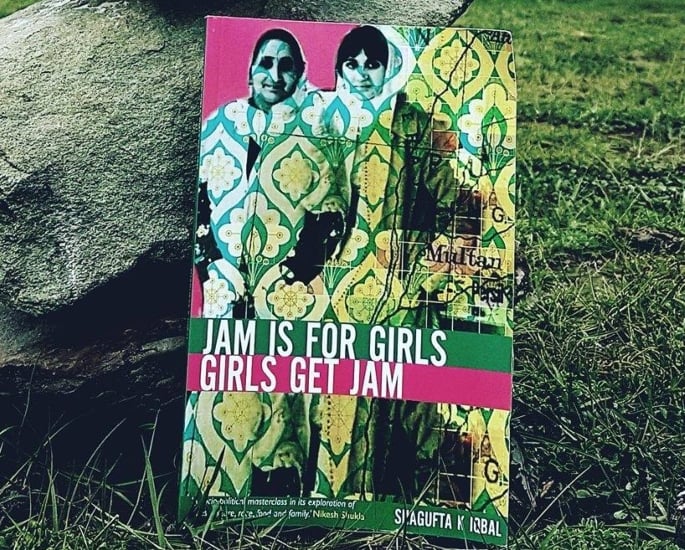

Shagufta Iqbal’s ‘Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam’ is Art

Described as an “elite performer”, Shagufta Iqbal is a spoken word artist, poet, filmmaker, and writer whose talents ring out through her debut collection Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam (2017).

The book is an honest and emotional insight into the immigrant experience and lends a voice to the journeys of women to unknown territory.

The poems concern themselves with the tenderness of identity and Shagufta weaves in themes of gender inequality, politics, racism, and injustice.

The detail, intricate imagery, and fragility that the poet is able to paint are delicate to the reader but remain unapologetic.

Likewise, Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam deviates away from the normal clash of cultures that can become a repetitive theme with British Asian poets.

Instead, it is “confirmation of the third generation identity caving itself a space in an increasingly Islamaphobic world”.

So, we dive further into the collection, discussing some of the major points and highlighting why it is a must-read narrative for South Asians and wider society.

Here to Stay

Perhaps one of the most consistent themes within the book is overcoming racism and discrimination, especially when trying to solidify your place in a new society.

Shagufta Iqbal writes of her parents’ transition from India to Bristol but also her difficulties trying to exist as a brown woman.

Referencing multicultural communities and racist interactions, some of the poems have such vivid imagery, it’s hard not to feel the emotion of the words.

For example, in ‘Stop and Search’, Shagufta references the hatred towards black communities and the fear she and her family felt during this time.

However, the poem still displays how the community knew to keep their heads down and deal with these experiences:

“It wasn’t so much our problem back then,

that everyday hate and discrimination

that was so ingrained in Thatcher’s impoverished Britain.

We were just Pakis back then,

kept our head down,

got our work done,

and got out when the time was right.”

This theme pops up again in ‘Stokes Croft’ where Shagufta struggles with cultural appropriation and the meaning behind it.

There’s a fragile battle the poet is fighting where she feels her place in British society is to just merely to exist.

However, especially at such a young age when Shagufta had these experiences, she feels as though if that is her role, then she will do it properly:

“We’re strewn round here for decorative purposes only.

No one will reach out with words and strike up conversations.

Two worlds side by side as if in parallel universes.

Yes, like light-years-away stars.

We’re strewn round here for decorative purposes only.

So shhhhhh, twinkle, and just look the part.”

Even though it’s quite emotional for a young Shagufta to feel as though her/her family’s existence is so small, there’s an overwhelming essence of empowerment.

She recognises her surroundings but doesn’t seem to do things half-heartedly.

What’s clever is she embodies the strength of her elders who made the difficult journey to Britain.

It’s almost as if she accepts whatever role she plays within the community but shows signs of moving towards a more significant part of society.

Womanhood

As Pavan on Goodreads wonderfully said:

“I’d rate this collection as the one that pulled me in the most. It’s beautiful.

“Poetry is meant to get to your very core, and this did. I had that shiver down my spine feeling as I read.

“This absolutely nails the female immigrant experience, and 2nd/3rd generation women’s identity.”

Womanhood, empowerment, and female experiences are highlighted throughout the book.

However, the poet is not afraid to tackle more of the pressing issues concerning gender inequality.

In ‘Medusa’s Rage’, she describes the sexual freedom women should have and how she is not afraid to start a “war” to get her message across:

“It’s not an invitation for you to violate my personal space,

like some pervert extraordinaire.

And I feel that there is violence

in your words, it hangs in the air.

Suffocates me, it’s hard for me to bear.

It makes me want to strike you down where you stand.

Backhand.

Make you understand

that if you gaze on my face I will turn you into stone.”

This power structure is everpresent in Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam.

In each poem, whether it talks about women, culture or history, Shagufta writes with self-belief which is immersive.

This same captivating nature is seen in poems where the writer is addressing her own community and the issues within it.

In ‘Excuse Me, My Brother’, she references how some Muslim women are questioned on the extent of their ‘beliefs’, using the body as a symbol.

But, she flips this around and focuses on men. Asking them provocative questions, Shagufta Iqbal writes:

“And tell me, why is your kuchi on display, my brother?

In fact, while I have your attention

and the right to discuss your body,

let me ask you,

just how circumcised is your dick, my brother?

Oh, I’m sorry, are my questions embarrassing you?

How does it feel to be told you don’t measure up

to my understanding and requirements

of what it means to be Islamic enough?”

The use of “my brother” is so sarcastic and potent because it juxtaposes the statements that the poet is making.

Yet, the use of the phrase refers to the language people use in conversation in Muslim communities.

There’s almost a plea from Shagufta for women to be less sexualised and questioned about their faith.

It also brings in the cultural view of South Asian women and how they need to follow certain guidelines in order to be ‘respected’. The poem finishes off with:

“Listen to my words,

see me beyond the vessel

that carries my soul and mind.”

The balance of faith, expectation, and reality is something Shagufta Iqbal deals with in unique ways.

The issues themselves are serious but the tone she uses in bringing these problems to the forefront can only be described as humorous authority.

Even in ‘Remember, My Daughter’, she speaks to herself from her father’s point of view.

This type of conversation is rare between a South Asian father and daughter and speaks to female readers and their self-perception.

Balancing western beauty standards, representation and identity, the poem reads:

“So remember when you find yourself bookended

between images of women with gold glittering hair,

who epitomise desire and the ability to obtain,

that no, you will not find your identity on that TV screen.

But understand where you belong,

not as a Miss World or a Miss Universe,

but as a woman to whom the world belongs.”

The different strands of womanhood and culture mix effortlessly within Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam.

Shagufta’s ability to speak to women and list so many relatable experiences mean the collection speaks to such a catalogue of women and helps them feel less alone.

Historic Culture

One of the most important themes of the collection is the emphasis put on the history of South Asian culture.

Firstly, all the poems are broken off into different chapters.

These chapters, barring the first, are titled with the names of famous Asian rivers such as River Sutlej, River Jhelum, and River Ravi.

Not only do these hint at the overall concern of those specific poems but refer to the relevance of each river.

The most poignant display of this literary tool is shown in ‘Empire’ which is under the chapter River Chenab.

This river flows through India and Pakistan and the poem is an emotional retelling of the 1947 Partition.

Shagufta Iqbal cleverly transforms the historic event into a type of relationship. Not only does this modernise it for younger readers, but gives the Partition a new perspective:

“I had let him hold

my face in his hands.

Whisper in my ears.

Let him mute the spice of me.

He slipped heirlooms off my nakedness,

fingers, neck, wrists, ankles exposed.

Put his dick into the soil of me.”

It shows just how difficult this period was for many South Asians. How thousands of people were banished from their homes, stripped of their identity, and stolen from their culture.

Shagufta then explains:

“I bore the children he denied.

He drew lines across my body,

broke me into nationless pieces.”

These compelling verses show how historic the Partition was and how the scars are everpresent over 75 years later.

Shagufta does amazingly at signifying the consequences of the event but highlights the strength of those that suffered.

Historic culture also refers to the history of skin-lightening and beauty standards in South Asian culture.

Describing everyday aspects of her life, Shagufta Iqbal explains in ‘Truth’ how the media plays such a huge role in beauty ideals, whether they know it or not.

Not only does this have an adverse effect on someone’s self-worth but how they think others perceive them:

“I wrote this poem for every time

I turned pages in Asiana magazine

and was confronted by skin-lightening products.

I wrote this poem for every time I switched on

BBC 1Xtra and BBC Asian Network,

and it was all light-skinned girl and goriya veh.

I wrote this poem when Diya magazine

quietly enveloped into my home,

my letterbox revealing how Indian models,

were replaced with European ones.”

This unrelenting address of ideologies within South Asian culture and putting certain companies or crowds on blast is what makes this collection such a must-read.

The combination of female experiences, history, racism, pain and much more does not overwhelm the reader.

Instead, it links a thread through all these themes to highlight how many pressing issues certain individuals have dealt with.

Likewise, it shows how they all play a part in South Asian and British Asian experiences.

Shagufta Iqbal is a tremendous poet, whose writing and distinct use of literature alters the way we view ourselves and the world.

Her ability to celebrate but also question her own communities are innovative, inspiring, and insightful.

Jam is for Girls, Girls get Jam is a gorgeous collection and a must-read for all, from poetry lovers to first-time readers.

Grab a copy of your own here.