A Review of Rakhshan Rizwan’s ‘Europe, Love Me Back’

Writer and editor Rakhshan Rizwan is back with her fourth book Europe, Love Me Back.

The poetry collection is a relentless outpour of questions and answers as Rizwan tries to piece together her identity and sense of belonging.

Originally from Lahore, Pakistan, the author lived in Germany and the Netherlands before settling in the Bay Area of North California, USA.

Europe, Love Me Back is an exploration of the continent and Rizwan’s uneasy relationship with it.

Using cultural settings, personal experiences and whimsical yet sharp language, she exposes the feelings of being politely received but not fully welcomed.

As explained by the publishing company, The Emma Press:

“This is an angry love letter, to a place left behind yet always there, continuing to matter and hurt and shape the poet’s identity.”

With such intense interactions, the collection gives great insight into a brown woman’s challenges.

The memories in Europe, Love Me Back are relatable to many South Asian women and to those who’ve struggled with the idea of home.

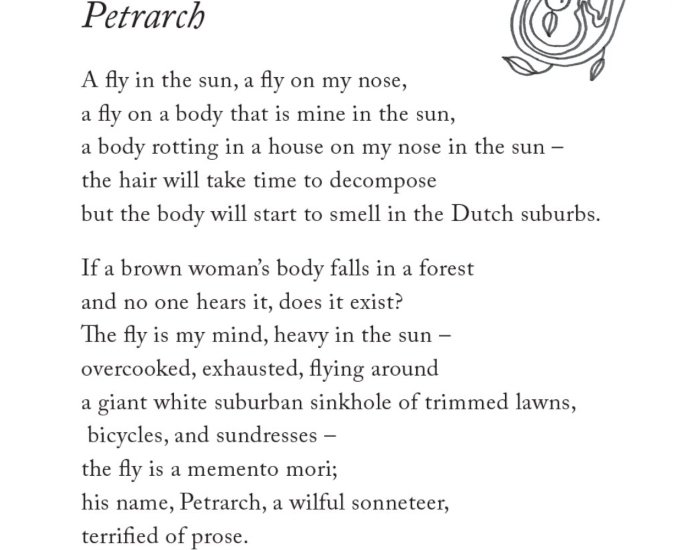

The poetic stories are one thing, but the structure of some of the pieces is equally symbolic.

Using sentence breaks, page orientation and paragraphs, Rizwan is able to signify her perceptions of each country and setting.

She then manages to link back to her inner thoughts and allows the reader to feel how she felt at that exact moment.

It’s what makes Europe, Love Me Back an intriguing read. So, we dive further into the collection and the elements that make it so significant.

Acceptance & Understanding

Two of the running themes in Europe, Love Me Back is Rizwan looking for acceptance and her understanding of the different culture and events she sees.

The collection starts with ‘Bite’ and here, Rizwan talks of her neighbour’s jubilation about summer but feels they won’t understand their shared emotions:

“I can see how you hang close to your friends

all the beautiful sundresses swishing and your tall

children by your side with their ice-creams

I can feel the lick of conversation on your tongues

history a wish-bone stuck in our throats

I am the most dressed person in the street

my skirt a deep green does not carry with the wind

a hijab tied into a summer turban will not toss in the wind”

It’s clear that the speaker’s hijab and turban set her apart from the rest and make for unsettling conversations.

It also highlights the cultural differences between her and those around her.

Rizwan wants to explain how she is just the same as anyone else but the effort of going through such an explanation is daunting.

Rather, she would leave it and let things develop naturally. The poem is rounded off with the lines:

“One day you will see the way

my skin pores open in the summer months

to receive warmth same

as yours.”

Straight away Rizwan puts how she is just the same as others but they won’t be able to understand that yet because of their lack of understanding.

Even though she accepts this (for now), there’s uncertainty about whether others will.

‘Adjunct’ is another piece that displays a lack of acceptance:

“When a country is so shuttered in

how do you get it to open?

I knocked and I knocked but nobody answered.”

The “door” is in reference to her search for work at a university but also embodies feelings of acceptance and entry as a whole.

Likewise, the poem comes from a place of loneliness and the essence of discrimination.

Rizwan writes “I tried to slip my academic degrees in under the door” which symbolises that she is an established individual but that is not enough.

She even writes:

“Someone told me to try other ways: pick the lock,

pry it open, but I did not want to be a brown crook

and prove them right.”

Her masterful technique to portray such feelings of prejudice in everyday things like applying for a job is mesmerising.

As Rizwan tries to navigate through life, her acceptance of these difficult experiences is thought-provoking and relates so much with minority communities.

For instance, in ‘Flaneuse’, the poem reads:

“The city wasn’t built for her

so she had to trick it, make herself a shadow,

a spindly ghost, fit into the lapel of the city.”

The lapel can symbolise the chest of a city, close to the heart, but just out of reach for the speaker.

She has to adapt to surroundings that were “imagined for others”, making it harder for her to belong.

These examples tease at how emotionally challenged Rizwan is.

The thrilling display of raw feelings and conflicted thoughts layer sentence by sentence until the reader feels overwhelmed.

Page Orientation

Another characteristic of Europe, Love Me Back that Rakhshan Rizwan uses is the manipulation of the pages.

Most of the poems are structured in a normal portrait mode but others are in landscape, spreading across two pages which is quite scarce in poetry collections.

The break in sentences that Rizwan uses is a famous poetic trait but using a landscape structure is fairly unique.

It seems that this is used for poems focused on South Asian culture, questions, experiences and views.

In ‘Caucasity’, Rizwan tells the reader of entering a classroom and feeling so isolated with eyes fixated on her because of the colour of her skin:

“I look away, pretend that none of this is happening,

that if I don’t acknowledge the exclusion, it didn’t happen.

Like I have to sign off on racism before it becomes real.”

The poem then describes the racist people as “predators” which is how many people feel who have been discriminated against:

“As prey, my mind constantly navigates the thread of predators

who don’t kill but casually humiliate, which is much worse.

I come to the conclusion that I am one of the two people of colour in the room.”

The standout line here is “predators who don’t kill but casually humiliate”.

Whilst this feeling is understandable, it actually provides some sense of comfort for certain readers who know they’re not alone.

Even in ‘Bookcase’, the speaker explains her time in education and talking with her supervisor about a thesis draft:

“You say, ‘Does Punjab have this many commas?’

as if a distant language is responsible for my disasters.”

Whilst the poem itself does not directly speak of any hostility, it’s micro-aggressive comments like this that emphasise Rizwan’s troubles.

The page orientation provides a different reading experience and seems the poet has done this to highlight more personal memories.

It could again embody a mind flooded with so much anguish.

The Power of Simplicity

Simplicity here does not mean that Europe, Love Me Back is a plain body of work. If anything, it is the complete opposite.

In some cases, poetry collections are overcomplicated with language and imagery that comes across as confusing.

But in Rizwan’s case, she keeps her sentences, similies and metaphors simple in order to create a more detailed and rounder picture of her feelings.

Her words form gateways of understanding where the reader is gripped by the stories presented.

Even in more profound pieces like ‘A Man is speaking Urdu on the train and everyone is turning to look at him’, her artistic quality shines:

“in beads of perspiration, crawls

into his tightening chest and grips

his skin till he switches to broken English.”

Words like “beads”, “crawls”, “tightening” and “grips” give a catalogue of emotions and intrigues you to a disheartening encounter whilst keeping you sensitive to what is going on.

Furthermore, the last poem of the collection ‘Seville’ goes along the same lines. It looks at the separation of countries and continents and queries perspectives:

“The separation of history into distinct floors,

as if this were possible to do with ourselves:

separate the Indian Lucknow from the Punjabi Lahore

and the Germanic European –

let them each rest a safe distance from each other.

In this quaint house, go up the steps

to feel more European,

come down the stairs

to feel more Arab,

and linger in between

to feel a bit of each.”

The poem clearly questions the perception of identity and how politicians can’t stop people from moving across borders as Rizwan has done in her life.

This house of nations in the poem talks about Indian, Pakistani and German floors.

Does moving to the European floor make someone European or is it based on country of origin?

What about people who haven’t been to their parent’s country of origin? Do they have to metaphorically walk up and down the stairs trying to seek a place that feels like them?

By using this simple analogy, Rizwan opens up a list of questions about the idea of belonging.

But it is this stripped-back technique that gives the collection such a well-constructed feel without jeopardising the essence of its meaning.

And her poetic consciousness resonates throughout the collection and oozes with all the qualities that make you question your own identity.

Europe, Love Me Back is certainly a love letter as previously described.

But it is from the point of view of a lover who felt like they tried to avidly make the right meaningful connections.

The speaker tried to search for common views, share thoughts, link commonalities and be with someone (Europe) forever.

But in this relationship, the other person (Europe) only saw reasons not to continue the affair and kept highlighting why it won’t work instead of providing reasons for it to blossom.

Grab your copy of Europe, Love Me Back here.